- Amman, King Hussain Park, Jordan

- +(962) 000-0000

- info@curafile.com

Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR)

- Home

- Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR)

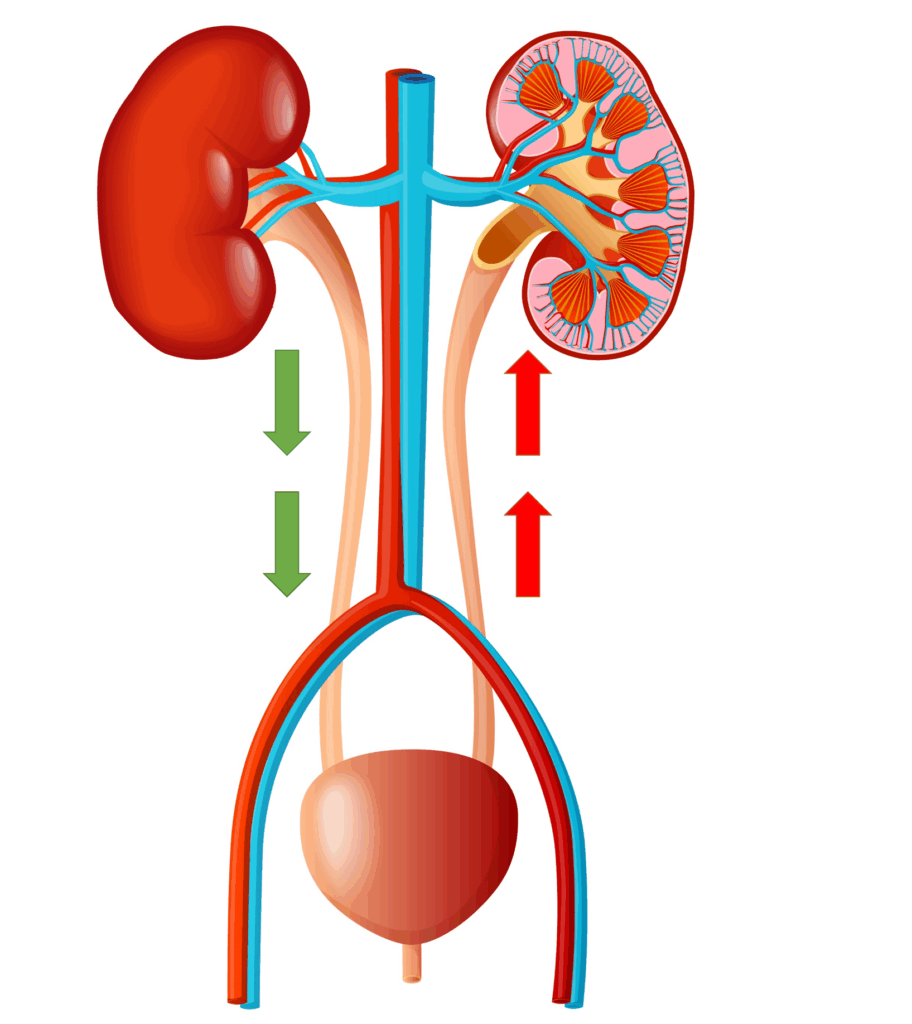

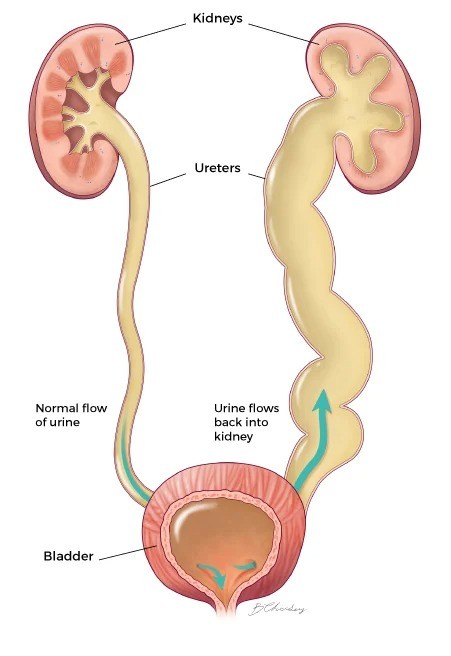

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is a condition in which urine flows backward from the bladder to one or both ureters and sometimes to the kidneys. VUR is most common in infants and young children. Most children don’t have long-term problems from VUR.

Normally, urine flows down the urinary tract, from the kidneys, through the ureters, to the bladder. With VUR, some urine will flow back up—or reflux—through one or both ureters and may reach the kidneys.

Doctors usually rank VUR as grade 1 through 5. Grade 1 is the mildest form of the condition, and grade 5 is the most serious.

VUR can cause urinary tract infections (UTI) and, less commonly, kidney damage. The two main types of VUR are primary VUR and secondary VUR. Most children have primary VUR.

About 1 in 3 children who has a UTI with a fever has VUR.1 The number of children with VUR may be higher, because some children with VUR who don’t have symptoms or problems are not tested.

Generally, the younger a child is, the more likely he or she will have VUR. VUR is more common in infants and children ages 2 and under, but it can also be present in older children and even adults.2

Children who have abnormal kidneys or urinary tracts are more likely to have VUR. Girls are more likely than boys to have VUR.2

A child is more likely to have VUR if a brother, sister, or parent has it. A little more than 1 in 4 siblings of children with VUR will also have the condition. A little more than 1 in 3 children with a parent with VUR will also have the condition.3

Primary vesicoureteral reflux

Most children who have VUR have primary VUR, which means they are born with an abnormal ureter. With primary VUR, the valve between the ureter and the bladder does not close well, so urine comes back up the ureter toward the kidney. If only one ureter and one kidney are affected, doctors call the VUR unilateral reflux.

Primary VUR can get better or go away as a child gets older. As a child grows, the entrance of the ureter into the bladder matures and the valve works better.

Secondary vesicoureteral reflux

Children can have secondary VUR for many reasons, including a blockage or narrowing in the bladder neck or urethra. For example, a fold of tissue may block the urethra. The blockage stops some of the urine from leaving the body, so the urine goes back up the urinary tract.

A child also can have secondary VUR because the nerves to the bladder may not work well. The nerve problems can prevent the bladder from relaxing and contracting normally to release urine.

Children with secondary VUR often have bilateral reflux, meaning the VUR affects both ureters and both kidneys. Doctors can sometimes diagnose a urine blockage in a fetus in the womb.

To diagnose the grade of VUR, doctors use imaging tests.

Imaging tests

Before you and your child’s doctor decide to use urinary tract imaging to diagnose VUR in your child, a doctor considers the child’s

- age

- symptoms

- family history of VUR

- sexual activity level in an older child

Doctors use the following imaging tests, or tests to see organs inside the body, to help diagnose VUR

- Abdominal ultrasound. An ultrasound uses sound waves to look inside the body without exposing your child to x-ray radiation. An ultrasound of the abdomen, called an abdominal ultrasound, can create images of the entire urinary tract, including the kidneys and bladder. An ultrasound can show whether a child’s kidneys or ureters are dilated, or widened. During this painless test, your child lies on a padded table. A technician gently moves a wand called a transducer over your child’s belly and back. No anesthesia NIH external link is needed. Ultrasound may be used to look for kidney and urinary tract problems after a child has had a UTI.

- Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG). A VCUG uses x-rays of the bladder and urethra to show if urine flows backward into the ureters. To perform the test, a technician uses a small catheter to fill your child’s bladder with a special dye. The technician then takes x-rays before, during, and after your child urinates. A VCUG uses only a small amount of radiation. Anesthesia is not needed, but the doctor may offer your child a calming medicine, called a sedative.

Lab tests

Health care professionals often test a urine sample, which is called urinalysis, to screen for a UTI. White blood cells and bacteria in the urine can be signs of a UTI. A urine culture is needed to confirm a UTI.

How do doctors treat vesicoureteral reflux?

Doctors treat VUR based on the child’s age, symptoms, and type and grade of VUR.

Primary vesicoureteral reflux

Primary VUR will often get better and will go away as a child gets older.

Until VUR goes away on its own, doctors treat any UTIs that develop with antibiotics, a type of medicine that fights bacteria. Treating UTIs quickly and preventing UTIs from developing will make it less likely your child will have a kidney infection.

Your child’s doctor also may consider the use of a long-term, low-dose antibiotic to prevent UTIs. Researchers have found that daily use of a low-dose antibiotic may help many children with VUR. Talk with your child’s doctor about using antibiotics. The bacteria that cause these infections can become harder to fight when antibiotics are used long term.

Sometimes doctors will consider surgery for a child who has VUR with repeat UTIs, particularly if the child has renal scarring or severe reflux that is not improving. Doctors can use surgery to correct your child’s reflux and prevent urine from flowing back to the kidney.

In certain cases, treatment may include the use of bulking injections. Doctors inject a small amount of gel-like liquid into the bladder wall near the opening of the ureter. The gel makes a bulge in the bladder wall, which acts like a valve to the ureter if a child’s valve doesn’t work properly. The doctor provides the treatment using general anesthesia and a child can usually go home the same day.

Secondary vesicoureteral reflux

Doctors treat secondary VUR after finding the exact cause of the condition. Treatment may include

- surgery to remove a blockage

- antibiotics to prevent or treat UTIs

- surgery to correct an abnormal bladder or ureter

- intermittent urinary catheterization—draining the bladder by inserting a catheter through the urethra to the bladder. You can do this at home if your child’s bladder does not empty properly.

You can’t prevent VUR, but good habits may help keep your child’s urinary tract as healthy as possible. To prevent some bladder infections and bladder control problems, have your child

- drink enough liquids based on the doctor’s advice.

- follow good bathroom habits, such as urinating regularly and wiping front to back.

- changed as soon as possible after his or her diaper becomes dirty, if he or she is not potty trained.

- get treated for constipation if necessary. Try to prevent your child’s constipation if possible.

- treated for related health problems such as urinary incontinence or fecal incontinence.

Clinical Trials

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

Contact your provider if:

- You or your child develops symptoms of nephrotic syndrome, including swelling in face, belly, or arms and legs, or skin sores

- You or your child are being treated for nephrotic syndrome, but symptoms don’t improve

- New symptoms develop, including cough, decreased urine output, discomfort with urination, fever, severe headache

Go to the emergency room or call the local emergency number (such as 911) if you have seizures.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials and what role do children play in research?

Clinical trials are research studies involving people of all ages. Clinical trials look at safe and effective new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving quality of life. Research involving children helps scientists

- identify care that is best for a child

- find the best dose of medicines

- find treatments for conditions that only affect children

- treat conditions that behave differently in children

- understand how treatment affects a growing child’s body

References

[1] Hoberman A et al. Imaging studies after a first febrile urinary tract infection in young children. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:195–202.

[2] Litwin MS, Saigal CS, eds. Urologic diseases in America. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases website. www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/urologic-diseases-in-america. Published 2012. Accessed June 4, 2018.

[3] Management and screening of primary vesicoureteral reflux in children. American Urological Association website. www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/vesicoureteral-reflux-guideline External link. Published 2010. Validity confirmed 2017. Accessed June 4, 2018.

[4] RIVUR Trial Investigators. Renal Scarring in the Randomized Intervention for Children with Vesicoureteral Reflux (RIVUR) Trial. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2016 Jan 7;11(1):54–61.

[5] Shaikh N, et al. Early antibiotic treatment for pediatric febrile urinary tract infection and renal scarring. JAMA Pediatrics. 2016 Sep 1;170(9):848–54.

Related Topics

Good Habits You Should Know

Bad Habits You Should Know

-

Find a clinic near you

-

Call for an appointment!

-

Feel free to message us!

About Us

Curafile is the biggest Healthcare Curated Network Globally that serves citizens, service providers in B2C and B2B directions.

- Al Hussain Business Park

Amman, Jordan

Additional Links

- test October 20, 2025

- Hello world! October 7, 2025

- Many doctors use wrong test to diagnose kids food allergies February 12, 2017

- Rising cost of diabetes care concerns patients and doctors January 15, 2017

- Can breakfast help keep us thin? Nutrition science is tricky January 5, 2017